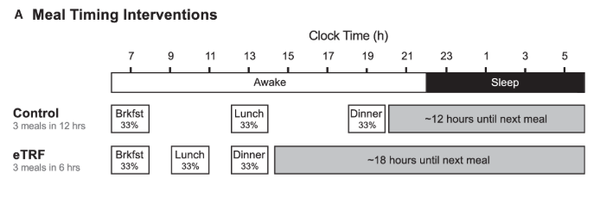

I’m coming to the end of the second week of a type of intermittent fasting called early time restricted feeding (eTRF). This involves limiting food intake to the morning and (late) lunch – for me between 8am and 3pm: a 7 hour window. What distinguishes this type of intermittent fasting from others is that it coordinates with our circadian rhythms.

There was an ancient household-known saying in China, called “fast after noon”, which came from one of the Buddhist precepts.

I am trying the diet as a one month experiment, having just been inspired by this recent research article (May 2018) published in the journal Cell Metabolism: Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress.

In this trial the following benefits were reported:

Essentially, eTRF resulted in greater blood sugar control, better immune response, lower blood pressure, lower levels of inflammation, less evening appetite (when digestion is less active) and – typically – weight loss. Other intermittent fasting studies have demonstrated increased fat oxidation (fat burning). eTRF may also result in increased autophagy – (1).

Peterson’s study is the first human trial of early time-restricted feeding. There are many approaches to fasting. This meal timing strategy combines intermittent fasting (14 or more hours of daily fasting) with eating in alignment with the circadian clock, eating when hormonal systems are geared to digest food.

I find this kind of intermittent fasting more practical than restricting calories one or two days a week (e.g. 24 hour fasting, or the 5:2 diet) – simply because it becomes habitual and as my body adapts to it, it becomes effortless.

On this diet you eat dinner by early afternoon. Think of hearty breakfast at 7-8am, lunch at 10-11 am and dinner at 1-2.30pm (it might require bringing meals to work and working through lunch).

Circadian Rhythms & Fasting: Breakfast is the New Dinner

My review on circadian rhythms here provides an overview of how different physical and cognitive functions may be harnessed at different times of the day based on circadian rhythms.

According to Dr Courtney Peterson, co-author of the eTRF study:

“What we’ve learned about our circadian rhythms is that we are better able to do certain things during certain times of day. For instance, we perform better at sports in the afternoon, we sleep better in the evening when our melatonin levels are higher, and you have your highest blood pressure rise in the morning, which is why we see more heart attacks happening in the morning. But we also know that our blood sugar control is better in the morning.”

If you eat the same meal for breakfast, lunch and dinner your blood sugar levels spikes much higher at lunch and substantially higher at dinner. The effect is remarkable, and researchers have known about it now for several decades – and it is known that there are very strong consequences to the times of day that we eat, sleep and exercise.

The reasoning behind this eTRF study in Cell Metabolism is that eating out of tune with your body’s biological clock can have negative consequences on metabolism and tissue function, which can have negative consequences (due to oxidation and inflammation) for cognitive function as well as metabolism and tissue function, including how well your muscles, liver and fat tissues burn sugars.

But different tissues and organs in the body each have their own mini biological clocks that can have their own cycles modified by other signals, including the times you eat.

The problem is that if you eat later in the day – particularly in the late evening – your brain is telling your muscles, liver and fat to slow their metabolism down while these tissues are getting conflicting nutrient signals to rev up from the food you are eating. These mixed signals can wreak havoc on the body’s metabolism, impairing function – both cognitive and physical.

“I currently recommend that people eat most of their calories early to mid-day,” Peterson said.

Intermittent Fasting & Cognitive Enhancement

Here are three well-known benefits of intermittent fasting for cognitive function:

Neuroprotection: Oxidative Stress & Inflammation. The human brain consumes 20% of the total basal oxygen (O2) budget to support ATP intensive neuronal activity. Without sufficient O2 to support ATP demands, neuronal activity fails. The brain is particularly susceptible to oxidative stress for a host of reasons (2), and eTRF (early intermittent fasting) helps reduce oxidative stress on the brain. Moreover, intermittent fasting reduces inflammatory bimarkers in the brain which may be neuroprotective against stress (3).

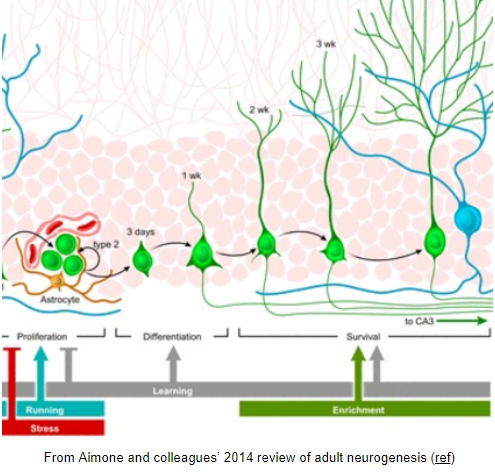

Neuroprotection: Autophagy. Disruption of autophagy—a detox process your body undergoes to clean out damaged cells and regenerate new ones – can cause neurodegeneration. Upregulation of this pathway is neuroprotective, and one well-recognized way of inducing autophagy is by food restriction – short-term fasting induces profound neuronal autophagy (4).

Neuroprotection: BDNF. Intermittent fasting results in increased production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which increases the resistance of neurons in the brain to dysfunction and degeneration of neurodegenerative disorders (5).

Neurogenesis and neuroplasticity. Fasting can result in the generation of new and functional neurons, possibly by the down-regulation of IGF-1 and PKA signaling (6). It can also have a stimulatory effect on synaptic plasticity (7). These mechanisms may explain the many trials demonstrating enhanced cognitive performance in rodent models (8, 9).

What I Have Noticed So Far

For my own experiment with early intermittent fasting, I’ve noticed the following in two weeks:

- First day difficult with evening carb-cravings, and a very unsettled night’s sleep. After two weeks, minimal evening cravings.

- Overall now, increased quality of sleep.

- More vivid dreams.

- Overall higher, more consistent energy/motivational level during the day.

- 3 kg weight loss. (I’m coming off an injury so it’s easier to lose this.)

- Heart Rate Variability good.

- Due in part to weight loss, better sleep and possibly other benefits, my fitness level has improved. I’ve been on a 14 mile trail run, followed by a 6 mile run then a 4 mile run all within a week – which is more than my usual training regime.

- Generally a feeling that it’s doing me good. I am certainly enthusiastic at this point, relative to other dieting regimes I’ve tried such as later day intermittent fasting, the 5:2 diet (and even 1:1 diet), and a prolonged period of the ketogenic diet.

I have now shifted forward to a 10am – 5.30pm fasting window, due to family practicalities. This also conforms with circadian rhythms, and is easier to maintain.

Comments are closed.