This is a response to Jordan Peterson’s provocative video on the role of IQ in being successful. Here I look at what is wrong with his view.

Peterson is right on a number of scores – particularly regarding his insight that ‘cognitive capital’ is now an important feature of our economy, and individuals with high IQs contribute substantially to national GDPs.

.

But Peterson is deterministic about IQ. He believes that you have a fixed IQ and that there’s nothing you can do to improve it. His claim is that you need to find the right job for your IQ level in terms of complexity and level in the ‘hierarchy of competence’ – or you will be out of your depth and miserable. The evidence presented in this e-mail should convince you that this view is very mistaken.

.

The fixed-in-stone view of Peterson’s is wrong on a number of scores – but here I want to concentrate on just one. And it’s not brain training! (I have dealt with the evidence for IQ gains from brain training based on the best available meta-analysis evidence in a number of places before).

.

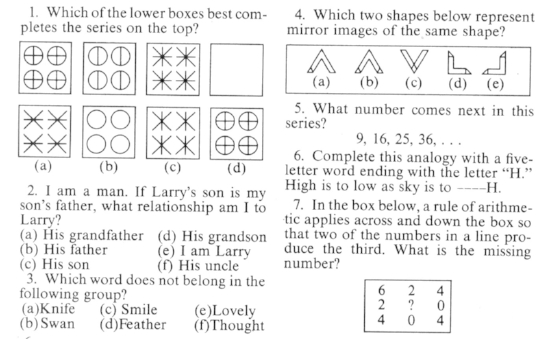

First let’s clear something up about what IQ actually is. Your IQ is a standardized score on IQ tests designed to measure general intelligence (g) – the underlying ‘general’ factor that underlies the positive correlations between scores on all the sub-tests found in a complete IQ test (working memory, visuospatial, reasoning, vocabulary, mathematical, etc).

.

.

.

‘G’ Is Not Found In Brains Or In Genes

Peterson talks about an IQ score as though it was a straightforward measure of a person’s brain power – something like ‘neural efficiency’ within an ‘intelligence brain network’. But this is simply not true.

.

- No specific general intelligence ‘g network’ in the brain has been found. Nor has some property of the brain such as neural efficiency, white matter conduction speed, or brain entropy, been pinpointed as the brain basis of differences in intelligence (e.g. Nisbett et al, 2012).

- Similarly, studies have not identified any specific set of genes that underlie the genetic basis of differences in g. As concluded in this comprehensive 2015 review on the genetics of intelligence: “‘identifying specific DNA variants that contribute to the high heritability of intelligence….will be a difficult task….heritability of intelligence is caused by thousands of DNA variants, many of these effects are likely to be infinitesimal or even idiosyncratic”.

.

General intelligence – the ‘general factor’ g – is an abstract statistical construct that measures correlations between scores in populations – not individuals. As the brilliant IQ scholars Kovacs & Conway (2016) put it:

.

“—the last survivor of a meteor collision with Earth would still have cognitive abilities and mental limitations but would not have g.”

.

The Evidence For Peterson’s View: Heritability and Stability

The key evidence that IQ is fixed in stone and cannot be changed comes from (a) the research showing a high heritability of IQ – i.e. the high genetic contribution to differences in IQ scores (review); and (b) research showing the high stability of individual IQ scores in adulthood – i.e. IQ scores don’t tend to change much from early through to late adulthood (review).

.

IQ Stability. Really?

Let’s talk about stability first, since it’s easier to understand.

.

A high impact article was published in the journal Nature in 2011: Verbal and non-verbal intelligence changes in the teenage brain. Cathy Price at University College London and her colleagues tracked the IQs of 33 adolescents between 12- to 16-years-old for four years. Fluctuations in IQ were enormous: 20-plus IQ points, one way or another – enough to take a person of ‘average’ intelligence to ‘gifted’ status, or vice versa. These changes in students’ IQ were associated with structural and functional changes in the their brains.

.

OK – so we’re looking at children here. They have highly plastic brains. But there is also good evidence that IQ in adulthood is not stable.

.

Peterson addresses his students in his lectures and tells them that there is nothing they can do to change their IQ. Well….this claim is contradicted by this international 2012 study by Clouston and colleagues demonstrating “a university education had a robust impact on adult fluid [intelligence] even after adjusting for adolescent cognition in multiple domains.” This study reveals that a person with average adolescent cognition who earns a university degree can expect similar adult fluid intelligence as someone with adolescent cognition measuring 8 to 23 IQ pointshigher who did not go to university. So just by virtue of taking his classes and getting a university degree, Peterson’s students may gain an additional 20 IQ points!

.

What about after college level? I would strongly predict that dramatic IQ changes would also also occur for adults who pursue 4-5 year post-graduate degrees such as PhDs into their late 20s – or mature students who pursue further education degrees later down the line. But these studies haven’t yet been conducted.

.

Why should be believe that? Because of the Flynn effect discussed below. In a matter of a generation or so, between 1950 and 1980 average IQ levels of adults in many nations has increased dramatically – up to 20 points in a number of cases – and this increase was due to changing environmental factors (more complex work environments, educational demands, etc), not genetics.

.

IQ levels more likely stabilize in young adulthood because we leave the intense and more generalist educational environments of school or university and find relatively stable cognitive niches’ for ourselves in terms of intellectual training and activity. More on this below..

High Heritability? Really?.

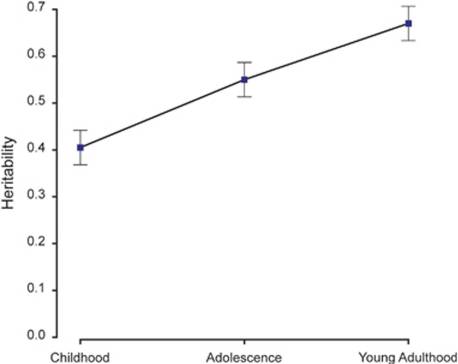

Heritability estimates the degree of variation in IQ scores in a population that is due to genetic variation between individuals in that population compared to environmental differences (such as cultural attitudes, resources, health care schooling, exercise, nutrition, brain training, etc). By young adulthood (20 years old) heritability of IQ is typically estimated at around 60-80% where it stabilizes (review). Let’s call it 70%.

.

Heritability estimates are the main evidence for believing that genes are firmly in control of IQ by adulthood, and that environmental impact (with an impact of only 30%) is relatively marginal. This evidence is the basis of Peterson’s claims that you better not end up in being mismatched with a higher level in the ‘complex dominance hierarchy’ and “people with lower IQs are more suited to more repetitive jobs.”

.

.

But let’s look at the heritability evidence more closely.

.

If our genes are in control, average national IQ levels should not change dramatically over one or two generations. But they have done – dramatically. For instance, 18-year-old Dutch men tested in 1982 scored 20 IQ points higher on the same fluid intelligence tests than did 18-year-old Dutch men in 1952. the average Dutch IQ between 1952 and 1982 has increased 20 IQ points. Israeli gains are similar. Every one of 20 nations analyzed show sizable gains since 1950. This is the well-known and much pondered ‘Flynn Effect’ – an effect which has recently been confirmed looking at all available evidence up to 2014. Genetic explanations – such as different reproductive patterns (e.g. out-breeding, finding more genetically diverse mates, natural selection, etc) can be ruled out here. The primary cause of this large, average IQ increase is environmental, not genetic (Flynn, 1987; Dickens & Flynn, 2001).

.

So what is going on? How can the paradox of high heritability with dramatic environmental impact be resolved?

.

Masking The Environment.

The answer lies in the way that heritability is calculated; it actually masks the true impact of the environment. For argument’s sake, let’s look at pairs of identical twins raised in different environments (e.g. through adoption) to estimate the relative contribution of genes and environment to their IQ levels at 20 years of age. If genetic influence was 100% we’d not expect any difference in IQ levels between the pairs, no matter how different their environments since their genes are identical. If environmental influence was large, we’d expect quite a bit of variation in pairs of IQ scores. Let’s say we find that there is some variation in pairs of scores but not much, and that we estimate that 75% of the variance in their IQ scores was due to genetics. Sounds like genes are in control right?

.

Wrong. In reality environment has much more impact than the remaining 25%. This is because there is a hidden two-way causation between the twins’ cognitive abilities and their environments. Higher IQ twins will generally be in more enriched, cognitively stimulating environments (e.g. stimulating friendship groups, supportive cultural attitudes, positive educational environments and so on) largely because of initial genetic differences that led them to those environments. Over time environments are ‘sculpted’ by our choices to match our cognitive abilities, and more stimulating environments in turn increase cognitive abilities.

.

“A higher IQ leads one into better environments causing still higher IQ, and so on. People who are born with a genetic advantage are likely to enjoy an environmental advantage as a result.” Dickens and Flynn

.

The way heritability is measured assumes that environments are random and independent of cognitive ability. In the case of the twins, it’s assumed that once twins are separated at birth and raised by different households that their environments are independent from their shared genes. But their shared genes actually shape both of their environments (social, activities, school routines, etc) to make them similar and correlated. And the more this happens, the more the heritability statistic masks the true impact of environment. (If you are really geeky and want to explore this topic – a very technical review is here.)

.

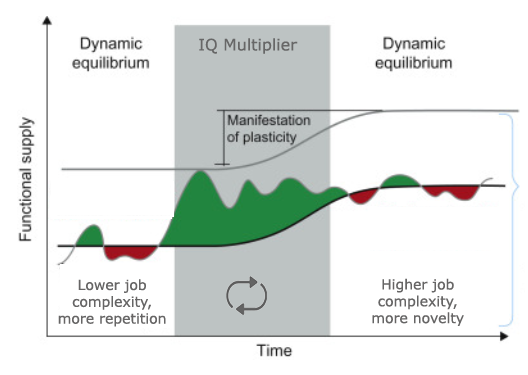

Multiplier Effects & Feedback Loops.

And there’s more to this masking story. It’s what’s called the multiplier effect and it’s sort of analogous to the ‘law of attraction’. Small initial IQ differences (e.g. 5 IQ points) can magnify quickly over time through ongoing IQ-environment feedback loops into very large IQ differences.

.

As Dickens and Flynn put it:

“[A] genetic advantage may itself be rather small. However, through the interplay between ability and environment, the advantage can evolve into something far more potent. So we have found something that acts as a multiplier.”

.

Let’s use Dickens and Flynn’s basketball analogy to underline the multiplier point. I will quote at length:

.

“a father who loves basketball and who has a son with slightly better than average genes for the relevant physical traits is likely to play basketball with his son at an early age, and they are likely to play together more often than most. The son may become a bit better at basketball than others his age and may frequently be an early pick when teams are chosen in the school yard. This makes him feel good, so he begins to prefer basketball to other sports. The extra practice makes him better still, and the better he gets, the more he enjoys basketball. He is far more likely than most to be singled out for membership on a school or recreational team where he will receive expert coaching. Such a young person is likely to become a very good basketball player—much better than he would be if his only distinction was the minor physical and social advantages posited at the outset.”

.

As this analogy suggests, this two way ability-environment multiplier processcan increase the influence of any initial difference in ability— whether its source is genetic or environmental. It’s not just initial genetic differences that benefit from this process – in this case, it could be due to the basketball loving father (something the the child’s genetics had no causal impact on at all). Anything (environmental or genetic) that makes someone better at something improves skills and ability that improve the environment that improves ability and so on in a multiplier effect.

.

The same process works with IQ and the trajectory can takes over just a matter of a years. A well resourced, educated, middle class family may provide a small cognitive advantage for their preschool child with an fairly average IQ, and this process may take that child down an IQ amplifying path to a giftedness program and Harvard, coming out the end with a high cognitive ability and an IQ score of 130!

.

The process we’re describing is a positive feedback loop.

.

Note that it could also be a downward-spiraling vicious cycle. Initially minor losses of opportunity or genetic disadvantages can amplify considerably over time. The Harvard student’s pre-school buddy who started off as a toddler just 5-10 IQ points less smart may, through cultural/family values, personal attitudes, streaming, labelling, and so on, end up as a factory Assembler – at that level in Peterson’s hierarchy of competence, with an IQ of less than 90!

The Instability of Heritability

The heritability of intelligence (h^2) increases from about 20% in infancy to perhaps 80% in later adulthood (review). There is a dramatic increase in heritability through to early adulthood as this study’s data shows:

.

.

Does this mean that our genes take more control over this time-span – as if IQ-linked genes become expressed more in our brains and behaviour (like the developmentally regulated genes for adolescence)? The answer is no: the same genes affect intelligence throughout the lifespan (review). So what explains the changing heritability of IQ?

.

The answer proposed independently by the great IQ scholars – Jensen, Neisser and Flynn is that it results from the increased matching of environment to IQ with age. As we get older our own cognitive abilities have an increasing impact in shaping our environments – at work, socially and culturally. And from childhood to adolescence, there is a steep drop in the role of shared environmental factors that are imposed externally on us such as family, school or university.

.

So this doesn’t mean that genetics take control of IQ levels in adulthood: it simply means that there is an increasing fit between our environmental ‘cognitive niche’ and our IQ.

.

Summary: Moving Up Peterson’s Complexity Hierarchy!

In summary, based on the arguments above I believe Peterson sends out a fundamentally misleading message. IQ is not fixed. We do not need to ‘find our place’ in the IQ hierarchy of job complexity and status based on some fixed IQ.

.

In fact, moving into a new, more complex and varied job may be an excellent way to launch from small advantage in IQ and harness a powerful multiplier effect. The advantage may put you in precisely that ‘top ¼ or ⅓ of those in your current job environment that Peterson refers to as optimal in his video. Being in this place may be due to an existing mismatch between your intelligence and your environment, or some recent gain in cognitive ability due to extra education, brain training, diet, exercise, and so on.

.

This graph illustrates the process. Green represents periods where demands may exceed cognitive ability, driving plasticity changes and increased IQ.

.

.#

There is compelling evidence that interventions (e.g. brain training and exercise) can result in small gains in intelligence. What the evidence reviewed above tells us is that these relatively small gains can be harnessed in positive feedback loops using the IQ-environment multiplier effect to lead to very substantial, long-lasting life changes in your IQ and career.

Flynn argues that some of these programs more than a year old may influence current IQ only because of their effect on past IQ and the effect of past IQ on today’s environment! Adult IQ is influenced mainly by adult environment. Training programs are more likely to produce long-term IQ gains if they teach how to replicate outside the program the kinds of cognitively demanding experiences that produce IQ gains while in the program and motivate them to persist in that replication long after they have left the program.

For four years I ran the Phoenix SIG, a special interest group within British Mensa for those who had been denied opportunities as children to develop their smarts and were looking for remediation opportunities regardless of age. I am particularly interested therefore in how the multiplier effect can feed into a downward spiral, and how seemingly minor withheld opportunities in early education can lead to so much potential not being realised later.

Comments are closed.